Mark Raidpere. Isolator. Text by curator Hanno Soans

“In my opinion such Estonian ‘men and women’ are enemies of the Estonian state and should be isolated: let them operate within closed walls.”

Märt Sults. A Duty to Preserve the Country, Postimees, 28 July 2004.

„The first thing the Germans did was to forbid Jews access to swimming pools; it seemed to them that if the body of an Israelite were to plunge into that confined body of water, the water would be completely befouled.“

Jean-Paul Sartre. Anti-Semite and Jew, Temps Modernes, 1946

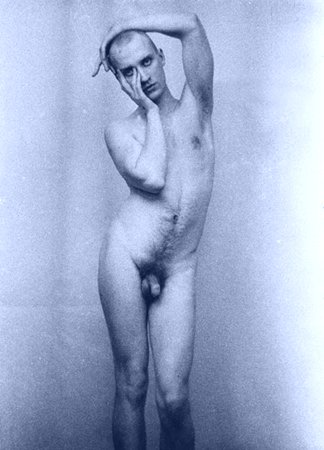

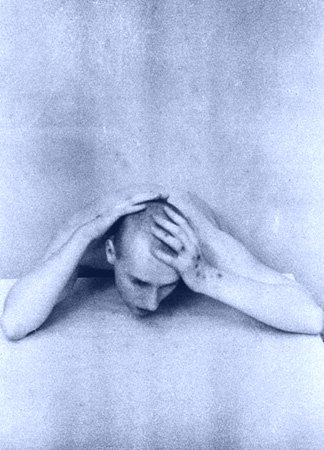

The intimate exhibition rooms in Palazzo Malipiero where the Estonian display is located act as a conceptual apartment. Mark Raidpere’s solo exhibition examining his personal identity contradictions marks the co-ordinates of privacy in social space. The viewer, who for the first time encounters the abundant grotesque of the homo-erotic motives of Raidpere’s earlier pictures of himself, is taken by surprise. Whence this pain, strained to its limits, discretely brought to attention by the cigarette-burned stigmas on the hands in the black-and-white photographs? This was the time Raidpere photographed himself at home, recovering from the crisis that led to self-burning – working with his father’s Zenit E that was probably just as old as he was. Later this became an exhibition titled „Io“ (1997) where personal material became public evidence. A theme of personal fragility was taken up in another key in the video “Father” (2001). It is a trip through the environment of a small flat in the district of grim dormitory-type houses, belonging to the artist’s father who had recently suffered a psychotic condition. The interview-based works of today return to earlier traumas mapping emotional breaking points between himself and his closest people. They are psychoanalytical strolls in the father-mother-home-and-myself quadrate of interpersonal relations, characterised by the high-tension between the private and the public, natural and staged, conditional and comprehensive. Everything eccentric hidden in the limelight – for example the condemned men at the prison photo session in the video “16 Men” (2003), who show him their tattoos – has fascinated him personally. Paradoxically the video has an effect of the artist’s self-portrait. Here a parallel emerges between home as man’s personal defence zone and prison as a social rejection zone. Raidpere’s heightened awareness of the performative nature of his identity reveals an agonising sign of danger, a symptom of something worrying, a state of a pariah. We get the impression that his presence always makes the others point their finger at him, thus increasing his need for solitude and privacy, romanticising even the forced isolation. According to Habermas, the isolation and privacy of a small-family sphere used to be the historical birthplace of content and free inner life, and part of the artist still believes in that. In contemporary reality, colonised by the camera lens, this romantic notion naturally remains in the field of unsatisfied Ego-Ideal, which escalates tension between the values of an artist and society. The ideological determination of the private sphere leads to non-solvable tensions between relatives and friends, something Raidpere tries to open with new means. Tension between the public and the private is stronger in transitional societies than in Western Europe with its longer experience of democracy and tolerance. In the motto of the current writing, taken from a homophobic article of a Tallinn school director and published last summer in a major local daily, we find a reference to the social background of Raidpere’s enforced dramatics. For a foreign observer, as a rule, this remains concealed behind the grand scenes of the PR-conscious New Europe, but is firmly evident in the private sphere. Joining the discussion, the editor in chief of the same daily later added that if the private life of homosexuals becomes a public affair, “there is no knowing when the majority’s thin coating of tolerance regarding minorities suddenly rips, and the streets are full of quite different parades” than the gay-pride. From Raidpere’s point of view this no doubt sounds threatening. We should perhaps try to regard the slogan introducing Estonia internationally – the land of improvement – without any irony. It might actually come in useful.

Hanno Soans