Ene-Liis Semper & Marko Laimre

Ene-Liis Semper and Marko Laimre came to art more or less at the same time, somewhere in the mid-1990s. The first as a dangerous heroine of ritual performances and with body-focused videos; the other with actions laced by meta-art strategies and installations with an anarcho-political flavour.

The work of both Laimre and Semper seems to indicate that a fundamental error, a complication, or at least a disharmony has been written into the elaborate mechanism of the present existence; and they are trying to capture it. Both have used their own selves and body as material, and have moulded the data of their personal histories into art. This is still very important to them. As strong personalities, the two artists have touched the borders of society’s threshold of tolerance and pain, either unwittingly or on purpose. The critics have seen them as radicals, and this is what they certainly are – both consider the rules set by society as repressive. Their artistic handwriting, however, has a fairly different colouring and manner.

Most of Ene-Liis Semper’s videos seem to exhibit the traumatic traces of the paradise of ‘purity and innocence’, losing the feeling of a mother’s womb and the eternal searching. The transgressive gestures of Semper whom the critics have called a cultural refugee seem to allude to the artist’s burning desire to cast off the strangling chains of culture and the burden of body, and return to the pre-language and role state. Her work bears the eternal stamp of the tragedy of being here, where the perception of self has been legalised as an imaginary misconception, and that alienated the subject into its own picture.

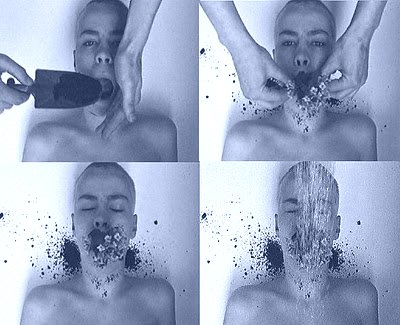

She grounds her revulsion for culture in self-portraits that are brutal to the point of self-sacrifice. Be it as a softly sounding ‘morose embryo’ (Nameless I, 1996); reading, slowly and in autistic incomprehension, the fundamental texts of cultural history (Fundamental, 1997); blending with nature in a forceful sacrifice (Oasis, 1999). She shows herself like a ‘bodily bored’ snake in its sinuous course upstairs (Staircase, 2000), or in a craze of sterility, licking the room into which she makes the viewer enter afterwards (The Licked Room, 2000).

Semper’s self-image, however, is that of a melancholic, quietly retreated into herself in mute pain, rather than expressively choleric. Her images are usually ascetically laconic and poor of symbols, a few exceptions notwithstanding, but at the same time powerfully immersing, and easily spellbind the viewer. The principle of an impact of her work is almost the same as in their making – fastening themselves to the depth of perception of the viewer’s body like leeches, they drag out the vacillations and impulses of her own dark nightmares. The charm of Semper’s work, often so difficult to analyse and even describe, lies in the very fact that they effect the viewer directly on the body level.

The ‘gust’ of that vague lost ‘something’ also hovers above several of Laimre’s works. Regarding his images – infants’ clothes hanging on flagpoles (Abortion Cards, 2000), a little boy in a photograph, clutching an empty shield who, on closer inspection, turns out to be the author himself (Black Material, 2001), or a vague momentary recollection of childhood (Mother Washing the Window, 2000) – then often in the direct meaning of the word.

While Semper takes transgressive strolls on the ‘ruins of self’, Laimre, on the other hand, seems to play around with his conception of an artist, or even parody it (Blood Flowers, 1999). A few examples: in a two-week endurance performance Bonj-njonj-nonj-non-now (1999), the artist chained himself into a cage like a beast. The cage held a sign which read: ‘Artist Marko Laimre’. In the performance L’île mysterieuse (2000) Laimre exhibited himself as a prayer in a straightjacket, forced to his knees in anticipation of the viewer’s punishment. Besides a real complication, the open exhibition of mad hysteria, in the manner of Žižek, also seems to point at the fact that overstepping all possible rules and regulations has become for the artist nearly compulsory. Laimre gives to understand that the artist’s duty to society is to be mad.

Semper transgressively steps out of social sphere and shuts her ears to culture in an autistic manner. Laimre additionally projects into his work the way the social pressure mechanism (Foucault’s Power) exerted on the Self functions, and tries to uncover its confusing and elaborate structures (State, Law, Medicine). Looking at various Laimre’s works (Sugarfree, 1996, Wollen Sie totalen Sport? 1999, Screenhouse, 2001), one cannot help recalling Barbara Kruger’s metaphor about body as a battlefield.

Laimre’s artist’s posture is that of an anarchist intellectual. He, too, reaches a cultural vacuum, but along very different routes. Laimre seems to shake the musical box of social nightmares until the sounds turn into a hysterically regressive babble, and, with an anarchist gesture, the culturally convertible meanings vanish, just like a knife cuts an imaginary wound into the viewer’s hand in his video Screenhouse.

It is not the first time for Laimre and Semper to have a joint exhibition. Their output contains similar, at times intersecting or quite opposing impulses. On the other hand, their work possesses that piece of the connecting stitching thread, that vague common part, that ‘something’, which Julia Kristeva calls a nameless and shapeless wound, without symbols and space.

Anders Härm