Estonia on the 48th Venice Biennial of Visual Art

Estonia is represented on the Venice Biennial by three middle aged, married man again. It might happen to be a embarrassing problem in the galaxy of Political Correctness, but people in Estonia don’t worry about that yet. On the contrary, in the bigger frame of Venice Biennial we are forgiven in advance as newcomers who may turn out to be a source of new blood.

It would be extremely short-sighted to enter the Big Picture under the slogan of male art anyway. The curiosity called “man” has been reduced in contemporary art to a much more marginal appearance like that of Estonia on the edge of a unifying Europe. A locational similarity that gives us direction to carry on with the subject. We are redrawing the map of European culture in “reborn Estonia” at the moment and this kind of world conquest is traditionally blamed on men. Any kind of challenging statement is. Nevertheless, no matter how deeply a modernistic attitude is corrupted in the eyes of the art audience, there will always be the next bunch of sincere pioneers who will be executed later for all the repercussions they did not foresee.

But what about art?

To go out of the cave and act like man has become a boring joke. It already merited a kind of cynical reception in our homeland, when I was publicly considering the necessity of the notion of male art. “What a scandal – Estonia is coming up with three married man in Venice!”, gloated the leading cultural weekly over the result of the national contest which selected the participants. The most enraged opponents were men themselves, so it is no wonder that “male art” became immediately a sort of guys thing which has its own means and ways of settling accounts.

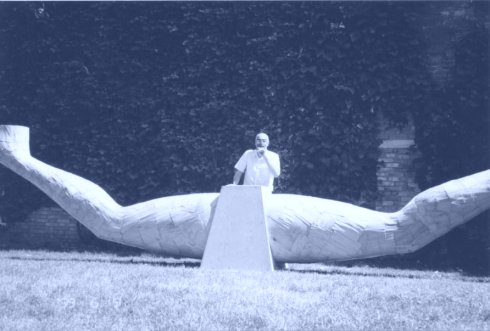

To the disappointment of my rivals I did not want to go very far from where I started. Neither do the artists. Peeter Pere shoots something, Jüri Ojaver refers to woman, Ando Keskküla implies death. Those are the issues which are used to extend into far reaching consequences in a modernist culture, but not this time. The viewer is presented with three crucial gestures with no specific target. There is no story, but gestures. Description of gestures, to be exact. So, those are not statements but reports on them. Does that mean that very shortly after involving the notion of male art I have to discuss its possible antecedents? Post-male art, history of male art - probably? I do not dare to get lost in similarly routine scenarios. But the autobiographical question “how did we get so far?” can be traced in the eyes of all three artists.

Johannes Saar